(Original article written for Patient Safety Learning)

You may think that I am saying this to be contentious, but sadly I am not. As an independent business consultant who supports new businesses and entrepreneurs in the health and care sector, this is a conversation which I have on almost a weekly basis.

The reason for this is that most innovations are in response to a perceived problem, and there is no problem more obvious than harm caused to patient during medical treatment. The British are by nature an innovative race (36,558 Patent Applications were made by UK citizens in 2019, ranking in the top 10 worldwide in several indicators), and for many people faced with a problem, their first response is to try and solve it, in this instance to prevent another patient from being harmed.

This means that people have an idea, design, prototype, or product, then find me to help them take the product to market and sell it. Unfortunately, many years of experience selling to the NHS across multiple organisations from primary to tertiary care, has taught me that the NHS will not pay to improve patient safety. This applies even in the instance of never events – events that occur with the potential to harm patients, where if all guidelines and protocols are followed correctly this should never happen.

My advice to innovators in patient safety

I tell all prospective and current clients working in the field of improving patient safety to prove their concept in the UK, then sell overseas. An insurance-based health economy aligns the cost of patient harm and litigation with provision of healthcare, and as such are risk-averse and highly motivated to provide the best possible levels of patient safety. The NHS system does not align costs and consequences of poor patient care with provision.

Why won’t the NHS pay to improve patient safety?

The NHS won’t pay because it is always the responsibility of somebody else’s budget.

In all things commercial you have to look at motivation and reward. If, for example, a surgeon is the responsible clinician in theatres where a never event occurs, that surgeon will be held accountable, and go through a rigorous investigation process to uncover the route cause. Although the investigation is not meant to be punitive, the sense of personal guilt, anxiety for the patient and family, and the potential for referral to governing bodies, and even loss of their job means that surgeons are very highly motivated to prevent never events. But the surgeon doesn’t hold the budget, if a piece of technology could prevent a never event in theatres, it would be the theatre manager who holds budgetary responsibility for purchase. However, the theatre budget is always fully accounted for, the NHS runs a very lean ship, and if an additional item is to be purchased, something else is not – so what should be left out? PPE? Autoclave? Staff? Another point for the theatre manager is that, although they would be part of any investigation, they are not held responsible for an event, and any consequential costs of extra bed days, rehabilitation and litigation are also not their responsibility.

To give a real-life example, I consulted with Uvamed in 2016. They have an innovative product which reduces the risk of medication errors in anaesthesia. I conducted research to uncover the scale of the issue in the UK, and in 2015 the Patient Safety Update from The Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) reported 7,992 anaesthesia errors between April and June 2015 (yes, that’s right a quarter of a year), of these errors, 2,235 caused harm to patients, including 21 deaths, and 22 severe harm. 13.5% of these errors were medication errors.

In 2016 there had been a recent change in NHS Litigation Authority premiums paid by each NHS trust for Professional liability and negligence, using a claims history of 10 years, instead of the previous 5 years, this meant that for some trust’s premiums had increased in excess of £2 million per year. This also meant that the litigation history of a trust would impact trust budget for 10 years.

A freedom of information request to the NHS Litigation Authority uncovered the total number of anaesthesia claims received in 2014/15 to be 148, the total cost of settling the successful anaesthesia claims over the 10-year period was £140,962,157.17, £6,598,988.38 in the year ending April 2015.

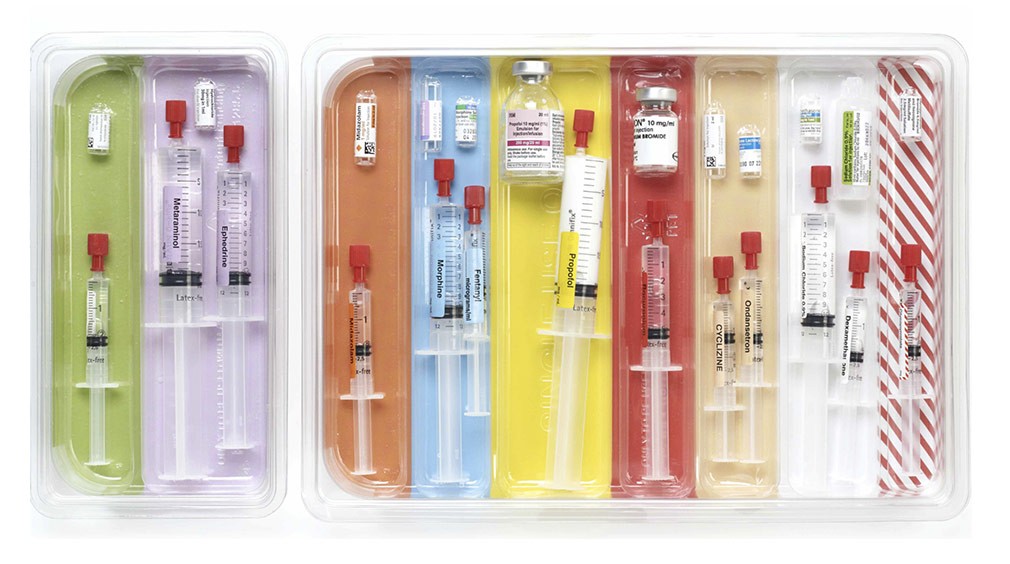

Anaesthesia is usually about a regular practiced routine. Standard practice is that syringes are prepared in advance of surgery and labels are applied to each according to strict colour coding, the syringes are then put in a receptacle (usually a cardboard kidney dish), with a second selection of prepared syringes in case of emergencies in theatre.

Most errors involve human factors, such as tiredness or distraction, and in the heat of the moment it is easy to reach for a syringe in a jumble of other syringes, and think that you have selected the right one, only for a different syringe to slip into your hand by mistake.

Rainbow Trays®

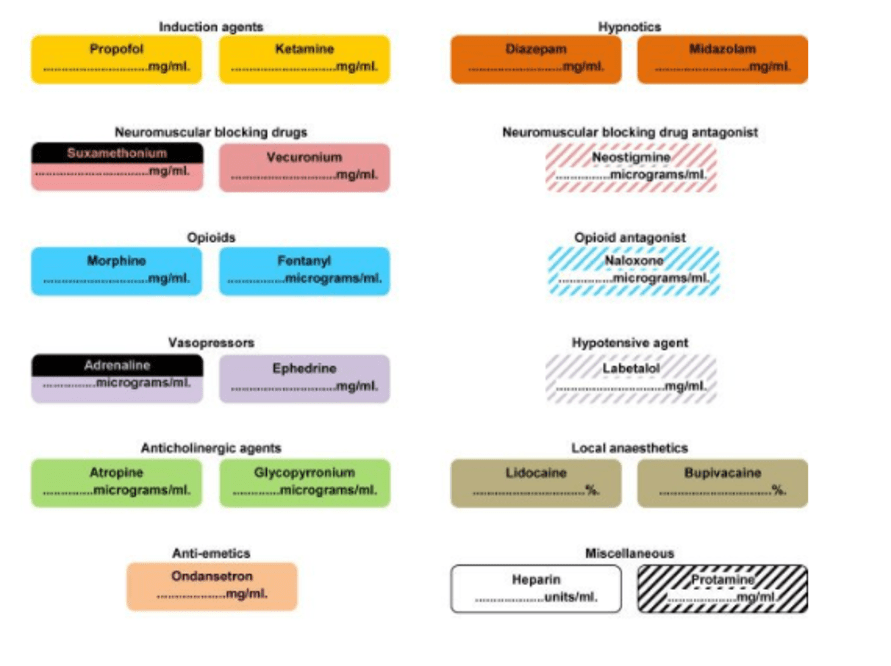

Rainbow Trays consist of a base tray with coloured sections, and disposable inserted trays which are made of bacteriostatic plastic, having physical barriers between sections. The colour coding is the same as that used in critical care labelling for syringes, with sections in a logical progression for use.

Critical Care Labelling

Who would buy Rainbow Trays?

Unsurprisingly anaesthetists loved them and wanted to trail and purchase. Trials went well, and everyone was happy. The purchase had to come out of theatre budgets. The theatre managers saw no financial benefit to their department in return for the spend so they wouldn’t pay, neither would any other department.

The happy ending for Uvamed and international healthcare is that Rainbow Trays are “flying off the shelves” in the USA, Australia, and New Zealand. Rainbow Trays are on NHS Supply Chain and have been purchased at quantity by Health & Social Care Northern Ireland for their Nightingale Hospitals.

Conclusion

NHS England will not pay to improve patient safety until either the silo mentally of internal budgets is removed (which is as likely as an effective fireguard made of chocolate), or someone at senior level in each trust is made accountable for the impact (financial and social) of unsafe patient care and given a budget to improve outcomes and reduce risks.